![]()

Joseph and Madeline Bertrand

Above: Joseph Bertrand Sr. (French)

The following is from the writings of Susan Sleeper-Smith, associate professor of history at Michigan State University, and coeditor of New Faces of the Fur Trade: Selected Papers of the Seventh North American Fur Trade Conference. Information gathered for her book, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes, was from thorough research of the Michigan historical societies and old documented church records for accurate historical preservation.

![]()

Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes

"...The Americans sought to control the lands that bordered the St. Joseph-Kankakee River portage but they acquired only a portion of those lands. The Potawatomi accepted some land concessions, because the Americans had complied with their agricultural demands.

Lewis Cass was infuriated by the large tracts of land retained by the Potawatomi, and the American negotiators blamed the unexpectedly higher population levels for their failure to extinguish the Indian land claims. Reed was both to pressure the Indians westward and to force Indian land cessions. Reed was initially encouraged by the Potawatomi request that the St. Joseph fur trader, Joseph Bertrand. speak for them. Reed described Bertrand as the only person who had any influence with the St. Joseph Potawatomi and anticipated that Bertrand would help him with the obstinate Indians, in exchange for treaty lands.

Joseph and Madeline Bertrand were the river valley's most prominent fur trade family. They had lived near the old St. Joseph mission, created by the death of William Burnett during the War of 1812 and the departure of Kakima Burnett to Fort Wayne. Joseph and Madeline Bertrand reestablished the type of Catholic fur trade community that had existed during the lifetime of Marie Madeline L'archevêque Chevalier, with kinship, Catholicism, and trade inextricably intertwined.

Reed encouraged Bertrand to initiate meetings that brought together the various Potawatomi villages, but, increasingly, found Bertrand's actions hostile to the national interests. Reed was excluded from the meeting and was unable to break the confidentiality of the Potawatomi meetings. He began to refer to Joseph Bertrand slightingly as the Talleyrand of the West.

Bertrand's efforts helped to thwart, first, the wholesale cession of lands and then, later, helped to shape the final treaty concessions that prohibited the forced removal of Catholic Indians. With Bertrand in attendance, Potawatomi village councils began to meet repeatedly and formulate a uniform set of demands. Like Reed, official American observers resented the secrecy surrounding these meetings and they were frustrated, like Reed, by an inability to learn anything about these conversations. Reed blamed Bertrand, "I have no doubt that Bertrand charged them to be silent respecting it." Reed did not understand the kin networks that generationally linked fur traders such as Joseph Bertrand and the Potawatomi. Nor did men like Reed appreciate the ability of the Potawatomi to act in a concerted manner. Instead, Reed blamed the continually delayed treaty negotiations on Bertrand, who was thought to be holding out "for a great price and to do the best he can for himself and family in the way of getting reservations." Reed disparaged Bertrand as "a sinister half-breed." Such racial slurs discredited the motivations of Potawatomi spokespeople such as Bertrand.

Joseph Bertrand encouraged Potawatomi firmness during negotiations. As a results, the Potawatomi received higher prices for ceded lands and, more important, retained title to selected sections. Surprisingly enough, the Potawatomi had also received similar advice from some of the early emigrants. This, of course, infuriated Cass's representatives. Reed told Cass that "the Indians have got a wild notion of asking a large sum for this tract...that the American settlers here, have persuaded them of the great value of this tract, and advised them to hold our for a high price." But Reed's displeasure focused primarily on Bertrand, whom Reed now described as an outsider with no claim to the land. To men like Reed the presence of any Indian on saleable land was unacceptable...."

"...Indian persistence has been obscured by American negotiators, like Reed, who promoted land cessions and assumed that Bertrand spoke only for himself. Reed equated Bertrand's behavior with self-interest, and this unjustified, biased viewpoint was accepted by later writers and historians. But Bertrand's behavior was defined by kinship and what he said and did was bounded and constrained by his role as spokesperson. Reed misunderstood the interdependence of fur traders and Indians.

In the end, the 1828 Treaty negotiated at Carey Mission made a surprising number of concessions to the Potawatomi who wished to remain in the river valley. Land was set aside for nineteen reservations. The government agreed to clear and fence additional lands and to provide both livestock and agricultural tools.

By 1832, the Potawatomi estate, although greatly reduced, still included more than 5 million acres. In southwest Michigan, the Potawatomi retained control over 10,000 acres; another, south of present-day Niles and near the lands granted to Bertrand's family, contained 32,000 acres. The size of these reservations led to a renewed call for additional land cessions. Unfortunately, both the Bertrands and the Potawatomi controlled some of the most fertile areas in the river valley. Known as Parc aux Vaches - cow pasture or cowpens - this had been the grazing area for wild buffalo. This rich, lowland area extended over 3,000 acres, and the early spring floods continued to create lush grazing pastures. The lands were also located at the crossing of the great Sauk Trail and thus provided a safe, central respite for Indian travel and trade.

Men such as Lewis Cass, Michigan's territorial governor, refused to leave this rich, fertile land under Potawatomi control. Despite treaty assurances to the Indians, Cass wanted all land east of the Mississippi available for public purchase, but repeated attempts to persuade the Potawatomi to sell were unsuccessful. At a Notawaseppe council meeting, Red Bird described not only the Indians' desire to remain, but also described the support his village received from their American neighbors...."

"...American treaty negotiators were equally intent on prying control of these lands from the Indians. Despite the 1828 Treaty assurances, it was increasingly clear that the government was refusing to tolerate even a limited Indian presence. Many Indian communities that also wished to remain in Michigan Territory relocated close to the Bertrand settlement. Their villages were clustered along the banks, streams, and tributaries of the St. Joseph River valley. This geographic proximity of like-minded communities facilitated communication and coordinated resistive behaviors.

The Potawatomi also would require assistance from outside the St. Joseph community if they were to oppose successfully someone as powerful as Lewis Cass, who was then territorial governor and later the federal official responsible for forced removal. The Potawatomi turned first to Isaac McCoy, who had established the nearby Carey Mission, but this proved to be an unwise decision. When McCoy and Topenabe's village endorsed A program of civilization through removal, Potawatomi interest in Catholicism became more pronounced. Most St. Joseph Potawatomi terminated their relationship with the McCoy Mission in the spring of 1823.

The Potawatomi turned next to missionary priests. Two years after the 1828 Carey Mission Treaty and McCoy's departure, the Potawatomi sought and received the support of the Catholic Church - initiated by a meeting with Father Richard in Detroit. Pokagon was a Catholic Potawatomi and an effective speaker who publicly pleaded with Father Richard for a missionary priest to live among the St. Joseph Potawatomi..."

"...To convince Father Richard of his sincerity, Pokagon fell down on his knees and recited a litany of Catholic prayers. Father Richard believed that Pokagon had never seen a priest and was convinced that the Potawatomi had kept alive the Catholic faith of their ancestors.

Pokagon's astounding recitation bore the visible traces of the influence that native female converts exerted among their Potawatomi kin. Pokagon claimed that his daily behavior included the "manner of praying as taught our ancestors by the black robes at St. Joseph." Pokagon probably never met a Jesuit, although priests from Vincennes may have traveled through the area. His behavior testifies to the presence of a Catholicism fashioned by Native converts.

There were numerous Catholic women, such as Madeline L'archevêque Chevalier, Kakima Burnett, and Madeline Bertrand, from whom he could have learned Catholicism's ritual prayers. Madeline Bertrand was the most obvious source, but there were other possibilities. For instance, Kakima was a Catholic convert and the sister of the headman, Topenabe, whose daughter Pokagon married. Like many residents of the St. Joseph River valley, Pokagon was adopted and then married into the family of Topenabe.Catholicism became embedded in the broader dynamics of social change and shaped resistance strategies. By the time Americans arrived in significant numbers, Catholicism had an institutional structure that it had lacked during the Franco-Anglo period. The St. Joseph River valley resistance involved the reestablishment of Catholic kin networks, the presence of missionary priests, and the construction of mission churches, as well as Indian schools.

CATHOLICISM BECAME and important refuge for those Indians who opposed removal westward. These converts turned to Catholicism because it was a means of accommodation rather than transformation. The Bertrands helped forge the Catholic community that figured prominently in the resistance effort. Their efforts were neither radical nor innovative but, rather, followed the patterns established by generations of Catholic fur traders. Madeline Bertrand functioned in the catechizing role established by Marie Rouensa and Madeline L'archevêque Chevalier in serving as babtismal sponsors. Madeline's daughter, Thérèse and her son's wife, Théotés, were frequent godparents for Indian converts.

Kin networks facilitated conversion and this was evident when the Bertrands became baptismal sponsors for the various members of Pokagon's village. Pokagon, his wife, Elizabeth, their children, numerous Potawatomi, as well as Bertrand family members were baptized by Father Rese, when he traveled through Michigan in 1830. Father Stephen Badin, assigned to the Potawatomi by Father Richard, later transcribed the names into his register from Father Rese's records. Rese baptized not only the fifty-five-year-old Simon Pokagon and his wife, but an assemblage of people indicative of the extensive intermarriage between the Bertrand family and Pokagon's village. The eight children of Daniel and "Théotés, sauvagesse" were baptized, the oldest of whom was nineteen. The priest had also delivered the marriage blessing to Marguerite Bertrand and Daniel Bourassa, Laurent Bertrand and his wife Thérèse, as well as to the newly baptized Simon and Elizabeth Pokagon.

In the nineteenth century, the efforts of village headmen supplemented and eventually supplanted female catechizers. These headmen converted entire villages. Kinship and Catholicism became inextricably intertwined. In southwest Michigan, there were at least six Catholic Potawatomi villages, headed by Pokagon, Wesaw, Shavehead, Wakimanido [White Spirit], Mkogo, and Pepiya.

These Indian communities were confirmed as Catholic, but they remained Indian regardless of how they were viewed by outsiders. Headmen influenced conversion and perpetuated the religious syncretism of a loosely structured Catholicism. That process is best illustrated by Leopold Pokagon, who was born when Roman Catholic priests were occasional visitors or, perhaps, nonpresent. When nineteenth-century priests arrived at Pokagon's village they lacked the strenuous missionary preparation of the early Jesuits, and therefore Pokagon emerged as an ideal proselytizer. He was verbally skilled, supplied an attentive audience, and appeared to be a sincere and devout Catholic. Most of these later missionaries spoke no Indian languages. Pokagon's position was comparable to that of eighteenth-century lay Catholic women, and like the efforts of those converts, Pokagon's behaviors were also encouraged by the priests.

Fortunately, for Leopold Pokagon, many traditional Potwatomi practices paralleled those of nineteenth-century Catholicism. Europe's new wave of Catholic piety encouraged Catholics to find their way to the sacred through an increased emphasis on ritual and n the intercession of saintly spirits. Three of the priests who ministered to the Potawatomi, Fathers De Seille, Petit, adn Baroux, left Europe in the midst of the Devotional Revolution. Adoration of the Holy Family, and particularly of the Virgin Mary, had reshaped Catholic peity. Believers venerated sacramental objects and sacred sites. Devotion to the Holy Family and the saints encouraged a Catholic generosity, community, obedience, and respect for family that also characterized traditional Potawatomi society. Innumerable feast days, fasts, and the appeal to saints highlighted the Catholic ritual. ..."

"...The 1832/33 treaty stipulation that Catholic Indians move to the Upper Peninsula was frustrated by a lack of available land. Pokagon's village vacated their Indiana lands, but moved only slightly north, to lands adjacent to those granted to Madeline Bertrand by the Chicago Treaty. Following the Chicago negotiations, many Potawatomi returned to their Michigan villages and then routinely ignored repeated government suggestions to move westward. ..."

"...Although Brady abandoned his effort to remove the Catholic Potwatomi, other Indians were less fortunate and were brutally forced westward. In August 1840, General Brady met with the Potawatomi of Pokagon's village and granted them written permission to remain in Michigan. He supplied a written pass which identified, by name, the Catholic Potawatomi exempt from removal. Ironically, the lists included Joseph Bertrand. It is unclear whether Bertrand lived among the Potawatomi, had been adopted, or simply feared for his own removal.

Potawatomi persistence can be tied directly to the Catholic conversion of many St. Joseph villages. Religion had political ramifications. Resistance and Catholicism became inextricably intertwined. But Catholicism also took root through institution building in the nearby town of Bertrand, made possible by Madeline Bertrand. She built St. Mary's Church and then provided a house for a convent and land for a Catholic school.

Although such magnanimity is usually considered reflective of a great piety, this was not the source for Madeline Bertrand's gift. Indeed, she was little remembered for her religiosity. Like many Catholic Potawatomi, she was not a devout Catholic. She attended mass at the small Catholic church in Bertrand, but the sisters remembered very little about her except that she was "a good singer during mass," who enthusiastically sang her two favorite hymns, "Hail, Heavenly Queen" and "Bright Mother of Our Maker, Hail."

Unfortunately, Madeline's life attracted little attention. Bertrand was not a town fondly remembered by nineteenth-century emigrants. Nor did the Catholic sisters wish to sentimentalize a founder who lacked religious devotion.

Despite Madeline's less than enthusiastic Christian demeanor, she transformed Bertrand, Michigan, into a Catholic community. The intent was to thwart the forced removal of Madeline's Catholic Potawatomi kin and to preserve Indian culture, not to transform it. Catholic priests were an integral part of these missions and they were highly literate men. Those who lived among the St. Joseph Potawatomi were educated and trained in France and Belgium. These men provided Indian communities the literary and legal expertise necessary to thwart removal. ..."

"...Catholicism's integration into resistance strategies was facilitated by the transformation of Bertrand Village into a Catholic community. That process took place following the Panic of 1837, after the Bertrand Real Estate Company went bankrupt and land speculation ended. Bertrand was no longer considered a prosperous community. ..."

(END)

![]()

Madeline Bertrand

Above: Madeline (Bourassa) Bertrand, 1/2 French and 1/2 Potawatomi

Madeline Bertrand's true origins are noted in the historical documentation preserved in Detroit, Michigan church records. Many theories and speculations have been made in connecting Madeline's origins as the daughter of Chief Topinabee. This belief and theory is known by educated historians to be false as there has never been any historical notes, church records, or documentation ever linking Madeline Bertrand to Chief Topinabee as a biological daughter.

Treaty documentation noting granted land to individuals within the tribe of the Potawatomi are known to be specific, to which whom land is granted. Potawatomi treaties specifically note relationships of individuals as "son of...daughter of...sister of...brother of...wife of ...or children of..." Biological family to Chief Topinabee documented in treaty records indicate only one family related known to receive land, noted as "Kau-Kee-Me, sister of Top-ni-be, principal Chief of the Potawatomi Nation". Her name appears specifically for land granted to her biological Burnett children. Madeline Bertrand's name appears in the Potawatomi treaties between 1821 and 1833 specifically the years of 1821, 1826, and 1828 only noting her as the wife of Joseph Bertrand, a Potawatomi woman, never as the daughter of Chief Top-ni-be. Old original Detroit, Michigan records documented historically by the church state "many residents of the St. Joseph River Valley were known to be adopted into the family of Topinabee".

Historically, the Bertrand family is known to have had close friendships to the family of Topinabee and the Burnetts. It is believed that Madeline Bertrand along with others from the St. Joseph River Valley were adopted like that of Leopold Pokagon, who would later marry Chief Topinabee's biological daughter, Elizabeth. The Bertrands were known as the River Valley's most prominent fur trade family.

The Catholic church records from St. Anne's in Detroit show that Madeline Bertrand was the biological daughter of Daniel Bourassa thru what was noted as "marital relations with a savage of the Potawatomi Nation". She was named Madeline. Her birth year was given as 1781. However, her tombstone at Bertrand shows she was 67 at the time of her death in 1846 making her born in 1778 or 1779. A mission priest from St. Anne's in Detroit ratified the marriage of Joseph and Madeline Bertrand on August 13, 1818. The following children were noted and recognized at that time: Joseph (11 1/2), Luc (8 1/2), Benjamin (6), Laurent (4 1/2), and Therese (1). School reports from the Carey Mission school in 1825 list "Joseph, Samuel, and Benjamin as students quoted 1/4 Potawatomi Indian". In the biological sketch of Benjamin H. Bertrand, US BIOGRAPHICAL DICTIONARY OF 1879, Benjamin stated his mother was Madeline Bourassa of French and Indian descent. In THE HISTORY OF TRINITY CHURCH, NILE'S MICHIGAN, it states "Joseph Bertrand's wife was a half-breed". This substantiates church records that she was the biological daughter of Daniel Bourassa, a Frenchman.

Above: Benjamin Bertrand (1/4 Potawatomi), son of Joseph Sr. (French) and Madeline Bertrand (1/2 Potawatomi & 1/2 French)

Jean Bertrand (French) and Marie Charlotte Brar (French) had a son named Jacques Bertrand between 1698-1699. Jacques Bertrand (French), a mason and stone-cutter, married Marie Louise Dumouchel in Montreal in 1729. Together they had a son named Joseph Laurent Bertrand in 1740. Joseph Laurent Bertrand, a French fur trader, married Marie Therese Dulignon on August 31, 1762. Joseph Laurent Bertrand was 21 years of age and Marie Therese Dulignon was 24 years of age at time of marriage. Together they had children: Eustach, Joseph Bertrand I who was also known as Joseph Bertrand Sr., and Marguerite Bertrand (Born between 1764-1765).

Marguerite Bertrand and Daniel Bourassa had their first child in 1780 then married on July 20, 1786. Before their marriage, Daniel Bourassa had what was noted as "marital relations with a savage of the Potawatomi Nation". As a result of this affair with the Potawatomi woman, Daniel Bourassa had a daughter named Madeline Bourassa (1/2 French and 1/2 Potawatomi) in 1781.

On August 13, 1818, Madeline Bourassa married Joseph Bertrand I who was also known as Joseph Bertrand Sr. Joseph Bertrand Sr. was the brother of Marguerite Bertrand, wife of Madeline's father Daniel Bourassa. Joseph Bertrand Sr. was a step-uncle to Madeline Bourassa thru her father's marriage to Marguerite Bertrand, but were not related by blood. From this time forward, Madeline Bourassa was known and documented as Madeline Bertrand.

Today's misunderstanding of Madeline Bertrand's origin has been traced to the late 1880s and early 1890s. Some very old local residents of Bertrand were interviewed in these early accounts. These interviews were known to be the origin of confusion of her being a daughter of Chief Topinabee. After these accounts, it was Known to have spun out of control as many writers interested in the Bertrand family have copied and continued the false documentation and reports of Chief Topinabee as the father of Madeline.

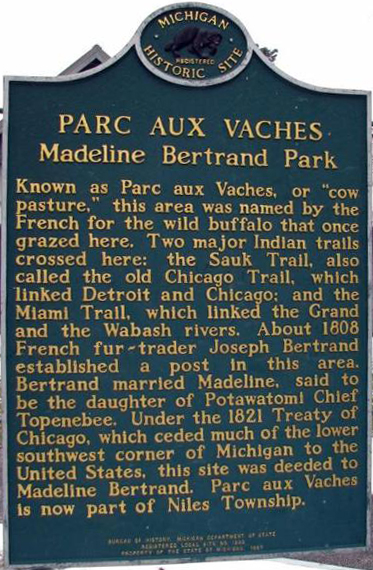

It is believed that many of the great Bertrand descendants have romanticized the idea of their great relative, Madeline Bertrand, being the biological daughter of the Principal Potawatomi Chief Topinabee making her a fantasized "Indian Princess", a European term. Within this romanticized fantasy, tales of her life have even stated she chose to live within the dwelling of a teepee or wigwam, established behind the log cabin belonging to her husband and family, rather than live within her family's cabin itself. Stories such as this have been created based on theory or pure imagination to add fantasy and create a little more Indian folklore to the life of Madeline Bertrand. Even two plaques were born and established in tribute of this rumored and romanticized biological kinship of both the Chief and Madeline within the Niles of Michigan. These plaques along with Madeline Bertrand Park were established in 1985-1986 when the rumor was in full speed. However, one of the plaques was noted without confidence stating: "Madeline, said to be the daughter of Potawatomi Chief Topenebee." This plaque contradicts the Bertrand plaque which continues the rumored tale that Madeline was the daughter of Chief Topinabee. On Madeline Bertrand's plaque, she is noted as "said to be". On Bertrand's plaque she is noted as "the daughter of". Obviously not enough research was done before these plaques were created and established in 1985-1986. But Madeline being the daughter of the Principal Potawatomi Chief would give for a much more exciting story people love to hear. Unfortunately, the documented facts show this is clearly false. Madeline's own son, Benjamin Bertrand, stated that his mother was Madeline Bourassa, daughter of Daniel Bourassa. This information came directly from her flesh and blood, not thru rumors created generations later.

Above:

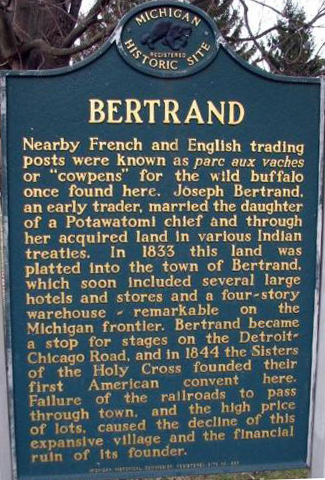

Tribute plaque to Madeline Bertrand. Plaque located in Madeline Bertrand Park, south of Niles, Michigan.Following is the other plaque which contradicts the above. The plaque below states "Joseph Bertrand, and early trader, married the daughter of a Potawatomi chief and through her acquired land in various Indian treaties." The facts on the plaque is reversed. Joseph Bertrand acquired land because of his prominence, not hers. In historical documents, Madeline is always noted as "the wife of Joseph Bertrand", never as "the daughter of Chief Topinabee".

Above:

Tribute plaque to Bertrand. Plaque located in Madeline Bertrand Park, south of Niles, Michigan.It is believed by educated historians that Joseph and Madeline Bertrand were considered to be part of the Topinabee family thru Indian adoption. Joseph Bertrand was considered a high status, well-known individual in the region of the St. Joseph River Vally and he attracted much attention, leaving his permanent mark in history. Because of his popularity and power he was both liked and disliked by many. Many Potawatmis considered him trusted family and many did not. During the treaty period of the 1820s, Joseph Bertand along with others married into the Potawatomi Nation and educated half-bloods were viewed as middle-men between the Potawatomis and Americans. During this period, educated half-bloods and those married into the Nation of Potawatomis would soon be the new leaders of a changing Potawatomi world as the voices of the old chiefs were becoming faint. Negotiations were not always done in the best interest of the Potawatomi people. Hundreds, thousands, and millions of acres of Potawatomi land were taken and gained by the Americans. Because of his knowledge and relationship with the Potawatomis, Joseph Bertrand Sr. was able to attain significant amounts of land during his assistance in the negotiations. Madeline Bertrand (1/2 Potawatomi) obtained land in the treaties of 1821, 1826, and 1828 because of her husband's prominence.

Madeline Bertrand died October 14, 1846. She is buried in the Catholic cemetery at Bertrand, Michigan. Joseph Sr. was known to have married once again on January 2, 1853 to a widow, Elizabeth LaPlante in Bertrand sometime in the mid-1850s. He and his second wife moved to St. Mary's, Kansas to be near his children. Their he was known to have died September 8, 1865, his second wife Elizabeth LaPlante died November 5, 1865. They are both buried in the Catholic cemetery at St. Mary's.

Joseph Bertrand Sr. left no will, but an estate settlement dated September 1869, appointing his son, Benjamin as administrator. Settlement shows that he left $600 in personal property and the following heir: B.H. Bertrand, son; the children of St. Luke; Joseph; and Lawrence Bertrand, deceased; and the children of Julia Higbee, deceased.

Above: Joseph Bertrand Jr. (1/4 Potawatomi), oldest living son of Joseph Bertrand Sr. (French) and Madeline Bertrand (1/2 Potawatomi & 1/2 French).

![]()